By Linda Thomas

Hometown Weekly Correspondent

Following each of the two world wars in which the United States helped save parts of humanity from the aggression of others, Americans felt a strong desire to make the world a better place, to create a brighter future.

A generation of Americans who helped save the world now raised children whose futures were, in their own way, also heroic — to help young people find their own paths in life and, maybe, save some who would lead our future.

Born in the midst of the Second World War, Harland Cook’s life began taking shape. At an early age, he was perhaps destined to be one of those people who would, indeed, succeed in making at least his part of the world a much better place and figure into the lives of some young people who thought they had no future.

Every hour Cook wasn’t in school he was on his father’s tractor, plowing and cultivating a staggering 50 acres of land and tending to 25 acres of apple and peach orchards including chicken, cow and horse barns with pastures — accomplishing all this in a single day.

And he was just eight.

“I studied hard,” he said. “I always wanted to succeed and do my best and get ahead.”

It carried on to his own years in teaching.

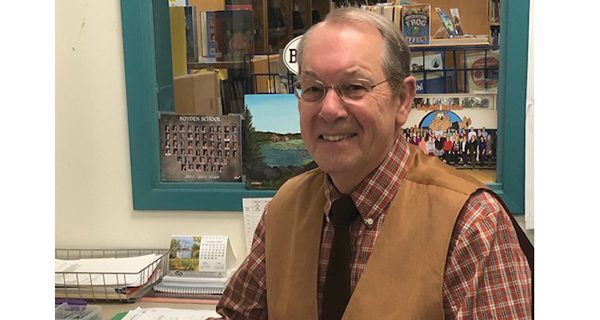

Since 1969, Cook has been on staff with the Walpole Public Schools. He spent the first 10 years teaching math, the next 25 as guidance counselor and special education chairman at the Johnson Middle School. And since 2004, he has served as a procedural assistant to the Boyden Elementary School and to the superintendent’s office. He also tutors and is treasurer and accountant for the Norfolk County Teachers Association.

Even at 74, Cook remains driven.

Farmer

Cook has lived in Walpole for the past 50 years. He grew up in Franklin and most of his childhood and adult years were spent working on his 200-year-old family’s farm.

Every day from when he was young, he and his brother took care of the animals: 12,000 chickens, 1,000 turkeys, 40 cows, 35 pigs, four horses plus 40 acres of fruit and vegetable crops.

“We were never in the house … always out on the farm doing something,” he said. “We hardly ever watched television. In fact, we didn’t have a television set until I was eight.”

The farm hired young boys and girls, teaching them the value of hard work and keeping them busy and out of trouble.

“I worked closely with the kids in the fields and at our farm stand encouraging them to make good choices,” he said.

“Just too bad these experiences are not so available for kids today.”

Teacher

Cook was encouraged and inspired by his high school math teacher wanting to emulate his energy and how he explained all concepts so everyone could understand them.

“I loved math all through school,” he said. “It was my favorite subject, and I wanted to teach kids in a way so they would enjoy math as I did.”

Cook received his high school diploma from Franklin High School in 1962, and then went on to earn a degree in math and education from Providence College.

Then came Michigan State University, where he enrolled in a master’s program. There, he began his teaching career at Bath High School in Bath, Michigan, where he served as head of the math department his second year.

Bath was a small, rural farming community at the time. High school was the end of their formal education for many kids. Half of his students came from homes with outhouses, with the school providing the only indoor toilets they had.

Cook tried to create scenarios to get his students motivated in the classroom. His goal was always to figure ways in which he could get around that to get kids to work for him.

“Where I was a farmer, I made an agreement with one student, who was in my honors math class,” he said.

“Though very bright, he didn’t seem motivated. So, I told him: ‘Ok, it’s plowing time … I’ll come and visit you this coming weekend and I will show you how to plow the fields.’”

That student believed there were no fields to be plowed in Massachusetts.

“I got on the tractor without him showing me anything and plowed some of his huge fields for about 10 or 15 minutes,” Cook recalled. “He was shocked, but from that moment he did his homework and went from an F to almost an A in the class. That’s what motivated him to work for me.”

Mary Faloon, Cook’s former student at Bath High, didn’t need motivation.

“Harland’s impact on my life was to make me more of an overachiever than I already was,” she said. “He made algebra 1 challenging and interesting. His enthusiasm just inspired one to do more with one's life and future and go to college.

“He got us students so involved with his enthusiasm [that] we went to the Lansing area math competition the spring of 1967 — and won. Those were ‘back in the day’ days when he had to drive the school bus himself, as we were a rural area north of Lansing.”

Faloon said she would tease Cook about his Boston accent with his “r’s” in warsh for wash, soda instead of pop — and laughing when he had to take a bus load of kids with brooms in the school bus to fight a brush fire in their farming community that next spring.

“He made a big dent on students being challenged and loving algebra with all those x + y = 6, ‘now solve for y.’

“I think he wore out a chalk stick every day on our green boards.”

Back Home

Then, in 1969, after receiving his master’s degree, Cook packed his bags and moved back east, settling in Walpole with his wife, Barbara, and their infant son — and a full-time position teaching math at Walpole High School.

“I tried to connect and inspire students to love math, and learning in general,” he said. “I tried to always be on task, organized, hold them accountable and present good lessons. I always found students liked structure and accountability.”

Chuck Giddings, who lived next door to Cook all his life, was angry, confused and sad after his parents’ divorce.

It didn’t take long for the then-11-year-old to seek refuge in a disreputable group of friends known to be involved with drinking, smoking pot and hanging around a street corner looking for trouble.

He was near the edge and unaware of potential consequences of the activities of his friends.

Then, once he started high school, he was given a chance for redemption, which came in the person of Harland Cook.

Cook saw his neighbor and student was heading down an unsavory path, getting himself into “mischief.”

He invited the boy to work on his family farm.

After school and on weekends and all summer, Cook would drive Giddings and other students to the farm in Franklin.

Giddings said his studies improved.

“It helped me focus,” he said. “It helped me know what I was going to do with my life, what I was going to have and how I was going to get it.

“Mr. Cook made a significant change in my life. Just having conversations up to and back from the farm. He was always checking up on me, making sure I went home with something I know he took out of his own pocket to give me … whether it was corn and vegetables or something more to help with my family.”

Half of everything he earned working on the farm, Giddings gave to his mother to help with the finances at home. But, he said, it wasn’t just about earning money. It was more about helping him grow and be more responsible.

“He changed my life,” Giddings said, now a 57-year-old carpenter with a family of his own.

“I saw what it was like being around a family that respected and cared for each other. I didn’t have that growing up. But I have that now — thanks to Harland Cook.”

Cook’s ability to find novel ways to connect served him well as he moved along in his career.

“As a guidance counselor, I tried to guide the students to make good decisions, solve problems, to get along, accept individual differences and not pick on each other,” Cook said. “And I listened to them.

“This is a very difficult time for kids in life, filled with changes and challenges. I actually spent almost as much time with the parents helping them to cope with their children at this age.”

Jean Kenney, retired assistant superintendent of the Walpole Public Schools, says Cook thinks about the students first and extends himself to all the families.

“He is someone who appeals to every single person,” she said. “He can talk to anyone, listens very carefully and is just an extremely thoughtful person. Harland is able to communicate with people to minimize the stress and their concern. He’s very empathetic. And when he delivers a message, he thinks carefully of the way it will be perceived by the recipient.”

This was particularly helpful in his special education work when parents first learned of the challenges they and their child would be facing.

Christine Ryan, a special needs teacher at the Johnson Middle School for more than 30 years, worked closely with Cook during his tenure as chair of the department.

Ryan and Cook worked with children of various abilities — and one child, in particular, comes to mind.

Cook encouraged the parents to participate, making them feel comfortable at the meetings.

“He would welcome them with a smile and a greeting making sure they felt part of the team,” Ryan said.

This student graduated from high school, now lives in an apartment, supports himself and is able to take public transportation by himself.

“He is very functional,” Ryan said. “He has grown to become a fine young adult.”

And she attributes this young man’s success to Cook’s ability to work with both the parents and the staff making sure all of this child’s needs were being met.

“Harland looks at every opportunity to ensure everybody involved is toeing the line when it comes to education for all.”

Family Man

For Cook, it’s always been about the kids.

Scouting was another discipline where he helped to instill values in young people, to prepare them to make good choices and to achieve their full potential.

He became an Eagle Scout, then Assistant Scout Master of Troop 44 in Walpole, where he spent several years working with young boys in earning their badges, taking them hiking, camping, and on outward-bound adventures. And he wanted his own children to have the same experience he had — learning to work, getting along with others and developing leadership and lifelong skills.

“My three sons and two grandsons are Eagle Scouts,” he said proudly, “and my daughter earned the Girl Scout Gold.”

Married for 52 years, Cook and his wife Barbara managed the farm until it closed in December, 1996. Their children grew up on the farm and learned at a young age the importance of working hard, working together as a family and keeping busy — a good life, he said.

“We’ve worked hard together all our married life and complement each other in everything we do” he said. “We raised four children, now married, and have 18 grandchildren. I could not see my life without my wife … she’s the love of my life.”

Cook volunteers for morning bus duty at the Boyden School, giving him a chance just to say “hi” to the kids.

“It makes my day.”

There’s not much inside himself that Harland Cook tries to overcome.

“Except,” he said, “not enough hours in a day to get everything done.”

Editor’s Note: Linda Thomas writes for Hometown Weekly Publications, Inc. For comments and suggestions, she can be reached at lindasfaces@gmail.com.