by Audrey Anderson

Hometown Weekly Reporter

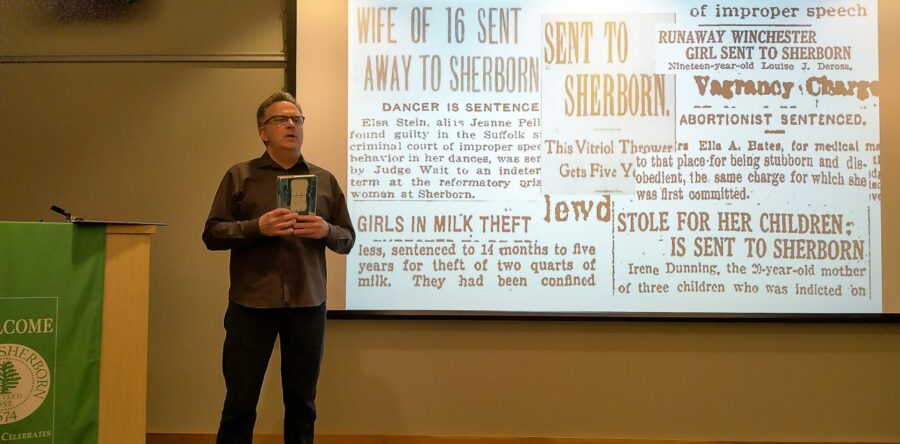

As part of the Town of Sherborn’s 300th anniversary celebration, the Sherborn Historical Society and the Sherborn Library presented a program on Tuesday, March 12, titled “Sent to Sherborn: The Sherborn Women’s Reformatory.” Estelle Friedman, Edgar E. Robinson Professor in United States History, Emeriti, Stanford University, shared her research on the reformatory in a presentation attended in person at the library and on Zoom.

Professor Friedman was a Ph.D. student at Columbia University in the 1970s when she researched the question of why separate prisons for women were established in the late 19th century. As part of this research, she visited MCI Framingham, formerly the Sherborn Women’s Reformatory, to learn about its history.

According to Professor Friedman, women reformers in the late 19th century advocated separate prisons for women to protect them from the abuses they suffered in regular prisons for both men and women. Women prisoners were often “fair game” for male guards and inmates, and the women suffered sexual abuse and enforced prostitution. Many women had children that were conceived in prison.

Reformers believed that women had the right to “womanly care” in prisons run by women solely for women prisoners. The goal was to reform and uplift “fallen” women. In Massachusetts, reformers worked on a four-year campaign to establish prisons for women. The bill passed in 1874, and the Sherborn Women’s Reformatory opened in 1877.

Originally, supporters of the women’s prison bill wanted the campus to be comprised of small cottage-type buildings, with an emphasis on domesticity. Instead, a congregate building was constructed.

The Sherborn Reformatory had a library, private rooms (not cells), a chapel, an infirmary, classrooms, and a theater. With good behavior, inmates could go hiking with a group from the reformatory. Many inmates were contract workers, washing laundry, making flags, and cultivating silk. Half of the inmates had young children who were allowed to live with them up to age 2. Suffragette Lucy Stone spoke to the inmates, and Louisa May Alcott read her stories to them.

The women that were “sent to Sherborn” were mostly white and many were European immigrants. Black women were more likely to serve their sentences in mixed-sex prisons. The Sherborn inmates were young, as half were under the age of 25. Seventy-five percent were first offenders.

The inmates were convicted for being alcoholics, idle, loose, stubborn, or disobedient. They committed crimes against chastity (cohabitation or pregnancy outside of marriage) or were runaways, to name some of the crimes mentioned in newspaper clippings of the period. Some of the older women were convicted of attempted murder and at least one woman, Dr. Catherine W. Castle of East Boston, was convicted of performing abortions.

An outstanding superintendent in the 20th century, Miriam Van Waters, was a “maternalist” who believed in the expansion of women’s authority from the home to society. Maternalists advocated laws for the protection of women. Van Waters called her charges “students,” not “prisoners.” She read to them from the Bible, allowed them to attend off-campus AA meetings, didn’t require uniforms, and allowed them to experience healing in nature.

In 1949, Van Waters was dismissed for allowing women to work outside of the prison, hiring former “students” to work in the reformatory, and including lesbians among the staff. Because her former inmates spoke on her behalf, Van Waters was reinstated, but her reforms were curtailed, and she was under investigation by the FBI. By the time Van Waters died, the Sherborn Women’s Reformatory became MCI Framingham.

For more information, see Professor’s Friedman’s books, “Their Sisters' Keepers: Women's Prison Reform in America, 1830-1930” and “Maternal Justice: Miriam Van Waters and the Female Reform Tradition.” You can also read more at https://history.stanford.edu/people/estelle-freedman.