By Douglas Brown

Community Contributor

In the center of Sherborn, at the only traffic light, there is an unremarkable street sign on the road to South Natick. When you are next there, waiting for the light to change, take a moment to reflect on the name. What you may not know is that “Eliot” is associated with one of the earliest and most significant pieces of American literature. And what's more - it has a fascinating connection to Sherborn.

This story begins in 1652. It was an important year for our town, as our first English inhabitants were making settlements along what is now Bullard Street (Route 115) near the Millis line. The entire area was wilderness, and Sherborn was one of the first settlements on a new frontier west of the Charles River. Most of the inhabitants of the area were indigenous peoples, including those from the Nipmuc and Massachusett tribes.

Change was happening in other parts of the world as well. England had just emerged from a civil war, which resulted in the beheading of King Charles I. Oliver Cromwell emerged as the victor and established the Commonwealth of England. Cromwell was a Puritan, like many who had fled England for America in prior years to avoid religious persecution. Now that Cromwell was in power, the Puritans in New England had new inspiration for pursuing their mission.

What was that mission? For many, it was to convert the Indians to Christianity. The feeling among many Puritans was that it was serving God's will to 'save? Native Americans from their wild and primitive ways and to teach them to be civilized citizens through the learnings of the Bible. While we know this today to be a narrow and ethnocentric view, it was a genuinely held religious belief by many at the time.

Two English men in Massachusetts played a leading role in this effort. The first was John Eliot, the man behind the street sign. He was a minister from Roxbury who was known as the “Apostle to the Indians” for his commitment to Native peoples and his efforts to teach them Christianity. Eliot partnered with Daniel Gookin, a government official with responsibility for supervising the Indians. Together, Eliot and Gookin helped to establish villages throughout the Massachusetts Bay Colony for the “Praying Indians,” the name given to those Native Americans who chose to practice a Christian way of life. The most famous of these praying towns was three miles down the road in what is now South Natick.

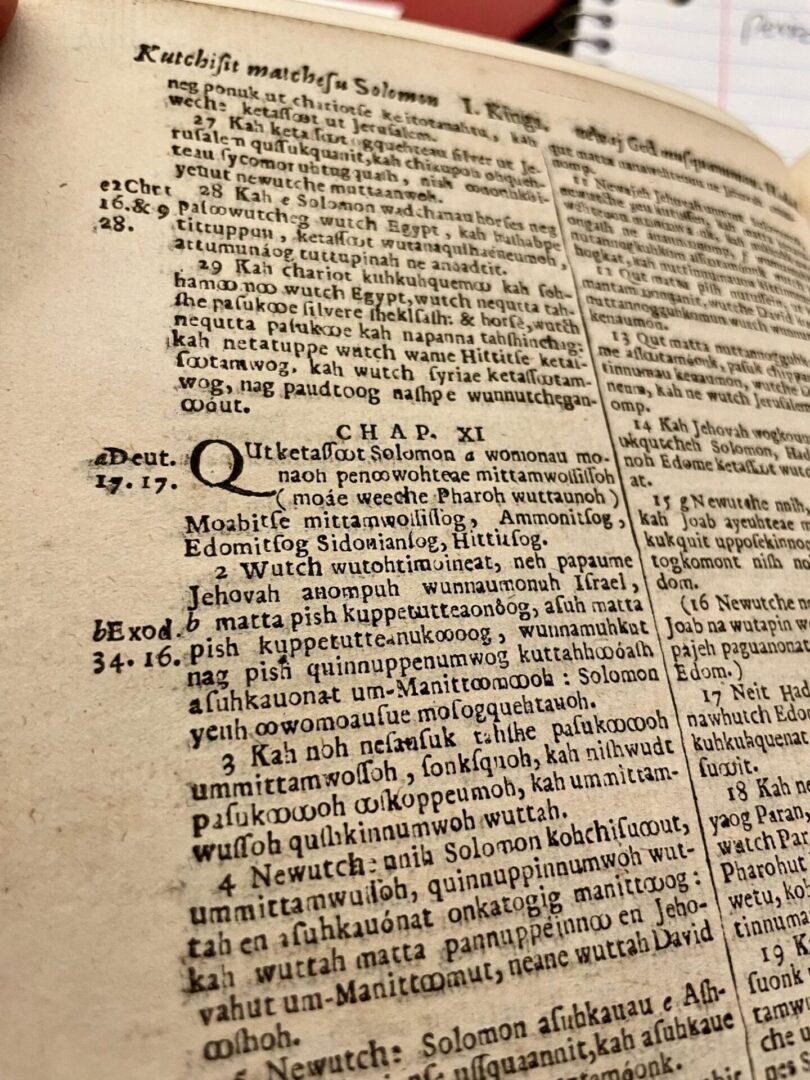

But Eliot had a problem. How could he teach the Praying Indians the lessons of the Bible if they could not read or speak English? Eliot answered that question by launching a 14-year quest to translate the entire Bible into the local Natick dialect of the Native American language.

It was a Herculean effort. The Massachusett language was largely an oral tradition, and existed in printed form for only about 10 years prior to Eliot starting his work. The translation was exceedingly complicated. And then there was the issue of the printing. The only printing press in America was at the newly established Harvard Indian College. The press required a manual process that could print only one page at a time. The Bible contained a total of 1180 pages, and each page required the manual setting of over 4,000 movable type-characters. Eliot and his team worked 13-hour days for months on end in order to complete the work.

The Bible was completed in 1663. One thousand copies were printed - enough for every Praying Indian family throughout New England. The first 20 copies were sent to Eliot's financial benefactors in London. On April 21,1664, one of those copies was presented to King Charles II to whom the completed work was dedicated (King Charles II came into power after Cromwell died, and the monarchy was restored in 1660).

The Eliot Indian Bible, as it has come to be known, was the first Bible printed in America and the first to be translated into a Native American language. It remains one of the rarest and most cherished books in America. To learn what happened next, and the Eliot Indian Bible's fascinating connection to Sherborn, please read the second article in this series, which will appear in next week's paper.