[ccfic caption-text format="plaintext"]

By James Kinneen

Hometown Weekly Reporter

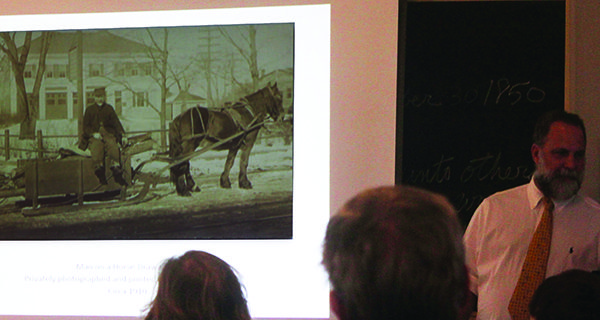

There are lots of ways to learn about a culture by examining the remnants of its past. But while most people understand historians’ interest in things like clay pots and arrowheads, on Tuesday afternoon, Wellesley Historical Archivist Allen Ludlow taught a crowded room inside of the Needham History Society just how much you could learn from the humble postcard.

Calling them “the social media of its day,” Ludlow outlined how postcards have changed throughout the years, noting how they were originally not allowed to be written on, a rule people got around by scribbling notes on top of the photos. It was only between the years of 1907 and 1915, when the now-universally-adopted split back was invented, that postcards truly came into their own. But it is not just this invention that made the postcards of this era so unique, as Ludlow explained. It is their inherent art.

Because the photos of the time were black and white, they would often be hand-colored. This lead to postcards that look more like matte paintings, as well as unique additions to the postcards. On one image of Needham Junction, Ludlow noted that while the photo shows the train tracks covered in snow, it is very possible that the person who colored the postcards added the snow himself, because he wanted to portray a winter scene.

This hand coloring could also have disastrous results, however.

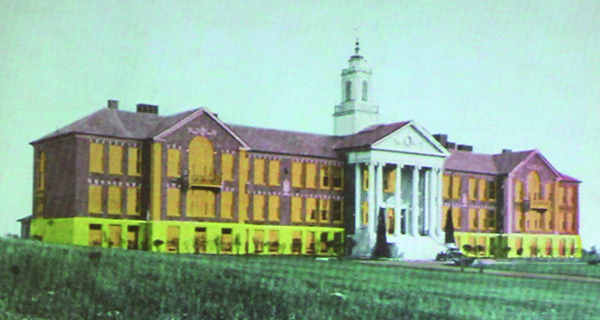

A few images show buildings in both Wellesley and Needham colored in vivid pinks and orange colors, likely a result of outsourcing the coloring overseas to someone who would have no clue what the buildings actually looked like.

However, some postcards were homemade by those wealthy enough to afford the rare Kodak camera capable of doing the job. This was the case in a few images, including one of the 1913 Wellesley football team and an image of a man and his horse-drawn carriage in front of the old Wellesley firehouse. Many of the images Ludlow showed are of locations no longer in existence, most notably Wellesley’s “Etherton” house, the home of famed ether inventor William Morton.

Other places have changed to be almost unrecognizable. Needham’s High Rock was noted on a postcard for its views of Boston. These days, however, the low trees depicted in the card have grown so high over the years that any former view would be blocked by them.

While the postcards offer a unique view of life in Needham and Wellesley from a certain time period, Ludlow did acknowledge that this worldview was limited.

“Writers of postcards in this area were almost all women of a certain high economic social class. Whether they were the only writers, or they were more likely to have kept the postcards while men threw them out is unclear, but the ones we’ve fond were almost all from women.”

Indeed, most of the postcards were girls from Wellesley College students sending correspondence to friends and family; the relatively uniform perspectives contained within could potentially distort a historian’s view of the area at that time.

Nonetheless, Ludlow’s presentation was a fascinating window into the area at a time when the postcard was the king of social media.