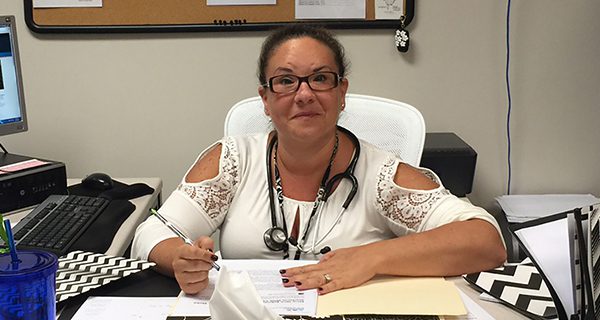

[ccfic caption-text format="plaintext"]

By Linda Thomas

Hometown Weekly Correspondent

Since middle school, Chris was her best buddy.

She knew something was wrong with him every time his harsh cough left him fiercely gasping for air. At 13, Rachel Jackson didn’t know that cystic fibrosis might kill her friend.

That was 30 years ago and Jackson, who now understands the magnitude and devastation this life-limiting disease could cause, must face the daunting task of confronting this debilitating illness yet again — this time as a nurse at the very school she and Chris were students.

Jackson is starting her second year as a full time nurse at Walpole High School. She’s spent the entire summer — actually, the entire year — implementing a plan of action to keep all students at the high school needing her care safe and relatively healthy while balancing the individual needs of three students with cystic fibrosis who for the very first time would be attending the school at the same time.

“Times have changed,” she said,” especially with the discovery of cystic fibrosis’ cross-infection and its potentially devastating consequences,” noting conflicts can result when cystic fibrosis patients come in contact with other cystic fibrosis patients.

Jackson says having had Chris in her life helped to solidify her choice to become a nurse.

“I think of him everyday,” she said. “I am caring for children that have the same disease he did in the same building we spent four years in school together. He is a major driving force behind my preparation for this year — and he continues to be a big behind-the-scenes support.”

That Common Thread

It was September 1987, the beginning of the school year at Johnson Middle School when Jackson (known back then as Rachel Johnson) was starting seventh grade. The school was just two houses down from where she lived on Robbins Road.

She already knew some of the kids in class, and met new ones. Chris was one. They became fast friends.

But Chris was absent a good part of that year. When he returned, he told his new friend he’d been sick with cystic fibrosis.

“He said he had cystic fibrosis, but he could have easily said he had a common cold,” Jackson recalls. “I didn’t know what it was. Being that he was absent for so long I knew it had to be more serious.”

Jackson’s curiosity led her to the library, where she scooped up as much information on the disease as she could find. She learned the significance of the disease, but didn’t quite realize her friend could actually die from it. Every time Chris ended up in the hospital, Jackson found a way for her and some of their friends to visit him. She came up with her own way into Boston’s Children’s Hospital — two buses and a train.

“Chris would go into the hospital to have a ‘clean out’ about every three months,” she recalls. “A majority of the patients at Unit 9 West at Children’s, where Chris used to stay, were people with cystic fibrosis, supporting each other and forming friendships.

“Little did anyone know at that time, but this common thread would soon be the very thing that would keep them apart.”

After school, Jackson would help Chris with chest physical therapy or sit with him while he did breathing exercises. Their senior year, Chris was elected class president and everybody loved him, she said.

The two remained good friends until Chris lost his battle with cystic fibrosis at the age of 27 in 2000.

Today, Jackson is making strides to ensure there is no chance students could cross-infect other students at Walpole.

As far back as Jackson knows, not since Chris has there been another student with cystic fibrosis at Walpole — not until last year when Deirdre Erwin entered as a freshman. Deirdre was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis two weeks after she was born. As the school nurse, Jackson was there for Deirdre if she needed her.

“Everything went fine last year … I barely saw or spoke with Rachel,” said Deirdre’s mom Maureen Erwin. “If anything had come up it would be between Deirdre and the teacher. We didn’t have to involve the nurse because there were no other children in the school who had cystic fibrosis.”

There were no health conflicts or potential cross infections. Erwin worked with the school and met with Jackson last year to set up a protocol — referred to as a Section 504 document — to protect her child’s well-being as she attended school.

When this school year arrived, so did two freshmen with cystic fibrosis. Then, everything changed for Deirdre — and for Jackson.

“Rachel was very proactive,” Maureen Erwin said. “I felt she went above and beyond the call of duty when it came to putting her plan into place for these three students.” Erwin says her daughter knows Jackson is in her corner. “She’s her angel up there,” Erwin said. “She’s her eyes and ears, and she’s able to communicate with the teachers even before Deirdre has met them.”

Jackson went one-step further checking with other schools to ensure there were no conflicts so Deirdre could serve on student council and play sports. “She didn’t need to do that,” Erwin said. “But I felt, again, ‘oh my gosh, that’s being over the top. You’ve got enough on your plate with 1,200 students.’”

She Gets It

With almost 1,200 students and over 150 staff members, the nurse’s office at Walpole High School is a revolving door, addressing everything from mental health issues to physical wellbeing and preventative care.

Principal Stephen Imbusch says Jackson fully understands this age group, as well as their needs.

“She speaks to them at their level,” he said. “There is a sense of mutual respect between Rachel and the students. Not everyone can relate to this age group. Rachel gets it. She works tirelessly to ensure the health and safety of every child and staff member under her care.”

Jackson’s action plan is designed to make sure these three students are not in the same classes, and that they do not have the same class back to back. Desks must be wiped down after every class to avoid the spread of infection that can occur in 90 minutes. She has worked with the guidance office to guard against these students from bumping into each other in common areas; there is a designated area in the cafeteria, should they have lunch at the same time, that allows them to avoid sitting at the same table or near one another.

“It is not surprising Rachel did a thorough job, because she does this for all our students. This is truly an example of best practice in school nursing,” said Walpole school nurse leader Kathleen Garvin. “Rachel has made sure the class schedules for these three students with cystic fibrosis do not overlap. She also has created zones for areas such as the cafeteria, auditorium, health office and restrooms.”

Though more than 30,000 people in the United States have cystic fibrosis, it is unusual to have three unrelated individuals under one roof, 7.5 hours a day, 183 days a year.

“As far as I know, Walpole is one of very few documented cases of three unrelated students in one school at the same time,” Jackson said. “When I spoke to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, they had not heard of any.”

Last month, Jackson wrote an article for the Foundation’s website to share her story about cystic fibrosis. Her words reached out to many school nurses from across the country, including one school in Wisconsin that reported also having three students with cystic fibrosis at the same time.

Since the article, Jackson has shared her action plans with nearly 100 school nurses all over the country.

Nurse Rachel

For as long as she can remember, Jackson knew she’d one day become a nurse.

Throughout her formative years Jackson suffered from a genetic eye problem that led her to visits to the doctor and several hospitalizations. She said she can remember the attention and care nurses gave her and told her mother, “I’m going to do what they’re doing.” She would play with her dolls and unlike other little girls she would pretend they were her patients.

Jackson went to nursing school in 1992 and four years later began working as a registered nurse.

She worked as a floor nurse, but once she realized she wanted to work with children, she started working for a pediatric home care agency in Boston - one of the first medical day-cares for children in the country, she said. That same agency opened a pediatric hospice division.

The first patient lived in Sharon, and because the needs of a hospice patient are so unpredictable, the agency wanted a nurse available who lived nearby. Though hospice work was something Jackson never thought she’d do, because she lived in Walpole, it became clear she was the perfect candidate.

“After a crash course, I accepted the challenge,” she said. “I cared for this patient for a little under one week before he passed away. I went to the home at 2:00 a.m. to offer my support to the family and to perform my first pronouncement of death. That experience was nothing short of life-changing. I felt I had found a calling, and so began my five-year experience with pediatric hospice.”

Then tragedy struck.

On the morning of Thanksgiving Day 2001 Jackson’s first husband, Joshua Hanson, a paramedic, was racing to save a nursing home patient in cardiac arrest when his ambulance collided with a car at the same site, killing him instantly.

At that time, Jackson was pregnant with their daughter.

Dealing with her own grief, she found it difficult to continue with hospice work. She needed a new career path. She needed to figure out how to be a single mom. After her daughter was born, Jackson spent the next 10 years in maternal child and home care. She later returned to hospice work full time and substituted at all seven schools of the Walpole school district. Two years ago, she accepted a full time position as Walpole High School’s nurse.

Walpole is still home to Jackson, where she lives with her husband, Randy Jackson, and her 13-year-old daughter, Joslyn.

Jackson says her friendship with Chris really helped to shape her career. But she never realized how much until this year. She imagines what it would be like if he were still alive, and feel they would still be friends.

“As a matter of fact, I feel like he would be working at the school with me in some capacity,” she said. “He was a pretty dynamic person — and it is no surprise to me that he still has an everyday presence.”

Editor’s Note: Linda Thomas writes for Hometown Weekly Publications. For comments and suggestions she can be reached at lindasfaces@gmail.com