[ccfic caption-text format="plaintext"]

By Richard DeSorgher

At first, it was referred to as the “pocket park,” a sliver of town–owned land wedged between Starbucks and Zebras along North Street. But thanks to Jean Mineo and a hard working committee, a positive vote at town meeting, and support from town residents, town officials and town departments, it is about to become Medfield’s newest park, known as “Straw Hat Park.” In a democratic move, the naming of the park was left up to the town citizens. Due to its proximity near what was the old hat factory, today’s Montrose School, the overwhelming vote was to name the pocket park “Straw Hat Park.” On July 13, starting at 6:30 p.m., the park will be officially dedicated with a ribbon-cutting ceremony, live music, straw hats and photos on displays from the old hat factory and ice cream for all.

The hat industry was an important aspect of Medfield’s history from 1851 until 1956. It was, in fact, Medfield’s most important industry, that, in its height, developed into the second largest straw and felt hat factory in the United States. At its peak in the early 1900s, the factory employed more than 1,200 people, larger than the population of the town at that time.

The history of the manufacturing of straw bonnets in Medfield began 215 years ago in 1801. Johnson Mason and George Ellis commenced what would become the leading manufacturing of the town in their tavern and store on North Street opposite Dale Street, where the 121 North Street apartments are today. In the beginning, the straw was braided by families. They either hired a few local women to sew the braid into bonnets or had all the bonnet-making done at home; only the finishing and packing were done at the shop. This system meant hiring men to make the rounds of the houses every two weeks by wagon to pick up the finished product and pay the women for their piecework.

In 1810, David Fairbanks kept a store on the east corner of Main and North Streets. Fairbanks bought large quantities of straw braid and employed a number of women and girls to sew it into bonnets. He had a boarding house for his female employees. The straw goods were carried to Providence by ox teams, then to New York by water. In 1829, Eliakim Morse also went into the business when he began to purchase domestic straw braid and manufacture it into straw bonnets at his 339 Main Street home, next to the Peak House.

In the 1830s, Warren Chenery began to manufacture straw bonnets. He constantly grew his business and did so well that in 1857, he constructed a factory three stories in height. It was located next to his house on 34 South Street in the area where Hale Place is today. Chenery later sold the factory to Jeremiah B. Hale. In 1879, the three-story hat factory burned to the ground and was never rebuilt.

In 1851, Walter Janes, for whom Janes Avenue is named, began employing about 30 women to make straw hats in the old Unitarian parsonage across the street from the First Parish Church on North Street. Shortly after Janes began the business, a young man from Mercer, Maine, named Daniel D. Curtis joined him. By 1856, the two formed a partnership and changed the name of the business from Janes and Company to Janes and Curtis. Under this form, the business continued until Janes’ death in 1865, when Daniel D. Curtis then carried it on. At the time of Janes’ death, 3,000 cases of hats were being shipped annually and an addition was built to the old parsonage, which doubled the shops capacity.

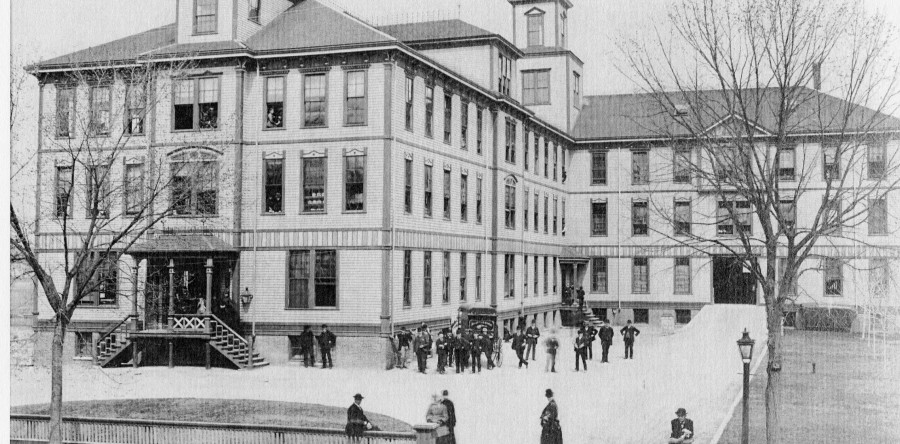

After Janes’ death, brothers-in-laws Haskell Searle and Granville Dailey of New York City joined Curtis. In 1876, their shop in the old parsonage burned to the ground. It was at this point that Curtis built the current building that still stands today along North Street and Janes Avenue. The New York partners attended to the sales and purchase of braid, while Curtis gave his attention to the manufacturing. Under the ownership of Curtis and later Searle and Dailey, the hat factory was known as the Excelsior Straw Works.

After Curtis’ death in 1885, Searle and Dailey were joined by a third major figure, Edwin Vinald Mitchell. He would go on to become the most powerful and important person in Medfield’s history. Under Mitchell, the hat factory would employ over 1,200 people, mainly young girls from small communities in Maine and Canada, and the Edwin V. Mitchell Company would turn out over two and one half million hats a year from the Medfield plant. Mitchell died in 1917 and under the control of his family, the business continued as a success until it was hit, with the rest of the country, by the Great Depression.

In 1930, it was sold to Julius Tofias & Brother of Boston. By the 1950s, the workers began to demand to be unionized. Tofias was very much against unionized workers and threatened to close the entire factory rather than accept a union. The workers went ahead and voted to form a union. Tofias closed the factory on June 8, 1956. The plant was converted into the Medfield Industrial Park. It was later to house Corning Medical and then Bayer Diagnostics before being sold to the Montrose School. The closing of the hat factory by Tofias brought to an end 215 years of hat making in Medfield and an end to Medfield’s largest industry. The new park’s name will now be able keep that history alive forever.