[ccfic caption-text format="plaintext"]

By Kevin Shale

A short walk through Highland Cemetery is also a journey through Dover’s history. Here lie the men and women who wrote that history. Yankees to the core, they were farmers, tradesmen, mothers, patriots, and soldiers, some of whom would give their lives in service to their country. We celebrate these heroes and enshrine them in our Honor Rolls. Dover has a long and distinguished history in answering the nation’s call to arms. Seventy-six men from Dover served patriotically in World War I, two died in battle, three in service. Some names were seldom spoken again, and for some, their stories have faded over time.

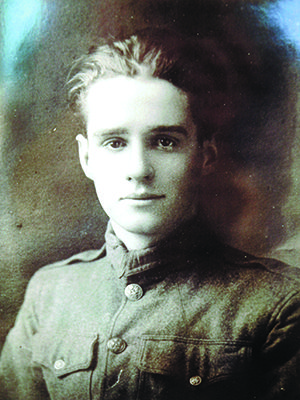

To many in Dover, the name George Preston will sound familiar. Some will recognize it as the name of the American Legion Post in the center of town while others may recall a photograph of him as the young soldier killed in the WWI. But in the hundred years since his death, little else has been known of the man whom Dick Vara described as “a home town kid who lived at Miss Lilly Mann’s on Pleasant Street.”

George Bernard Preston was born December 29, 1897, the youngest of three surviving children born to Edward and Catherine Preston, a poor Irish Catholic couple in Boston’s South End. Edward, born in Vermont in 1866 to Irish immigrant parents, had moved to Boston some years earlier to find work as a painter and paperhanger. His wife, Catherine Malloy, had immigrated to the United States in 1882 when she was just 12 years old. The couple had two other older children, Emma, born in December of 1893; and Thomas, born in 1896, was just beginning to walk at George’s birth.

Life for the Prestons would have been very difficult. Work was particularly hard to find for Irish immigrants, and the Prestons’ frequent moves map a steady decline in their circumstances. By 1902, they were living at 44 Hamden Street, in the South Cove area of the South End, a poor and crowded Irish neighborhood clinging to the Roxbury Canal where coal and garbage barges had docked. The Prestons would have been only able to afford a small room, possibly two, with a communal outhouse behind the building. A kerosene lamp would have lighted the room, with the only heat from a small coal stove. This was also the neighborhood of future Boston mayor James Michael Curley, who was living just a few blocks away on Albany Street at the time.

The winter of 1901-1902 was brutal and set records for both temperature and snowfall. It was also to become a turning point for the Preston family. Around Christmastime, Edward was rushed to nearby City Hospital. The reason is not known, but may likely have been a bad injury rather than an illness, as hospitals were beyond reach for most in his circumstances. While George’s father, Edward, lay in hospital, his mother Catherine, who had been long suffering from tuberculosis, declined as well. Only weeks later, on January 2nd, four days after George’s fourth birthday, Catherine died. The following day, their mother was buried and the children were taken by her brother and left at the “Home for Destitute Catholic Children”.

The Home, located on Harrison Avenue in the South End, was a Church run children’s shelter that would temporarily care for Catholic children and place them in homes if they became orphaned. The children’s father was released from City Hospital a month later, and immediately recovered his three children from the shelter. However, he is believed to have died soon afterwards.

The three Preston children were now orphaned as well as destitute. After their father’s death, they were entrusted to yet another charitable institution for placement. It is difficult to imagine the heartache and trauma the children must have endured that winter.

They would soon face more hardship – that of separation from one another. Emma, now eight years old, was soon placed with Julia O. Hunnewell, the daughter of prominent banker and philanthropist H.H. Hunnewell, at her home in Wellesley. The boys were later taken in by the Elbridge Mann family, who lived on a farm on Pleasant Street in Dover. Neither of these circumstances could have been more different from that of their lives in Boston, nor could the two placements have been more different from one another. Remarkably, the children were completely unaware that they were living only two miles apart from one another.

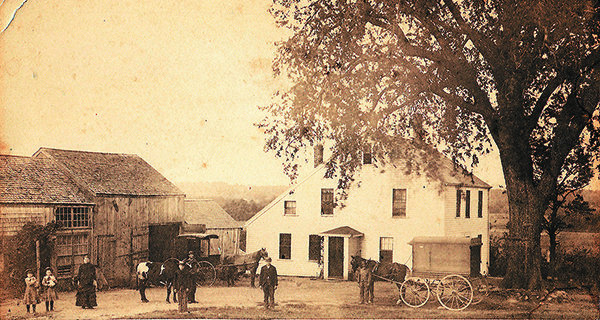

The Manns were an old and respected Dover family. Elbridge was well schooled in farming and a pillar of the community. His daughter Lilly, the boys’ guardian, would have been the same age as the boys’ father, Edward Preston. Lilly had been mother, cook, housekeeper and counselor to her father, Elbridge, and her brothers, Maurice and George, since her mother’s death twenty years earlier. She was known as a warm woman with a big heart, sense of humor and fondness for the boys. She was in many ways more mother than guardian for them. Her brother Maurice, who was a couple of years younger than Lilly, was remembered as being mechanically-minded, while George, the younger of Lilly’s brothers, managed the farm’s poultry business. This would be George Preston’s family for the rest of his life.

The farm, which stretched from Pleasant Street to Claybrook Road, was typical of a Dover working farm at the turn of the century and a perfect environment for two young boys.

Though life may not have been easy by today’s standards, to them it must have been heaven. The air was clean, the food plentiful and they had the warmth of a loving family. Everyone on the farm had chores and there was a lot to do. They would wake at dawn and draw water from the well. There were eggs to collect and a cow to milk, two horses to put out, and a pig to care for. All this was done while Lilly Mann was cooking up breakfast on an iron stove. Later, when the boys had learned to handle the horses, Elbridge Mann would have had them help out in the fields pulling the manure spreader. All these experiences would have been unknown to them in the South End. They were happy, and going to school for the first time in their lives.

During the times of year that school was held, the boys attended the Sanger School in the town center, where George can be seen in a class photo from 1904. George, a quiet looking child, had a full head of red hair, apparently as did his sister Emma.

As the boys had been baptized Catholic, and as there was no Catholic church in Dover at that time, the Manns, long time members of the Dover Church, would likely have taken them to Sacred Heart Church in South Natick, or would have arranged for them to be taken by another Catholic family living nearby.

Sometime before the war, it was discovered that the three children had been living in close proximity and a reunion was soon arranged. Emma, who had grown up in the care of a wealthy family with many servants, attended private boarding schools and summered on the coast of Maine. She sadly recalled after the reunion how little they now had in common.

On April 6, 1917, when President Wilson declared war on Germany, there was a tidal wave of patriotic response. The now 19-year old George enlisted the following day into the Massachusetts National Guard. Together with those of the other New England states, these untested young men from farms and factories formed the 102nd Infantry Division, dubbed “Yankee Division.”

In mid-April 1918, it began to rain. General Clarence Edwards, Commander of the 26th Division, later recalled that “…it was as miserable a night as they make in France, and there were miserable nights weather-wise. It rained all night and with the rain was fog which could be cut with a knife.” The Americans were aware of a growing German force, but there had yet been no signs of attack. The 102nd division had occupied the small village of Seicheprey and used the area at the rear of town as a reserve encampment and supply area. The fortification architecture was a series of forward trenches between Seicheprey and No Man’s land. The forward most of these trenches was the infamous Sybil trench, a “sacrifice trench” manned by 350 men randomly chosen from seven units and rotated in. They were sacrificial detachments. There would be no rescue for these men. If attacked, they were to hold their line at all costs.

Early in the morning of April 20th, at 2:00 a.m., the Germans opened a massive surprise artillery barrage on the Allied lines. General Clarence Edwards put it this way: “At 2:00 the silence and gloom were rent by the roar of the German Artillery far to the north of No Man’s land. In an instant the space between the Sybil Trench and the rear areas behind the town of Seicheprey was an exploding inferno. So accurately placed were the shells of the enemy that scarcely a foot of the mile and a quarter was untouched. High explosive shells, shrapnel and gas shells fell with regular intervals while above the inferno floated the deadly fumes of mustard gas which burned when it touched.”

Chaos unfolded behind the allied lines as the yet-inexperienced soldiers reacted to the shelling. When the Germans ended their artillery assault, 3,300 German soldiers carrying flame-throwers swarmed into town from the north, surprising the soldiers yet again. These were the German stoßtruppen, or stormtroopers. Their mission was to quickly infiltrate the enemy lines, to demoralize them by causing destruction, shock and chaos, and then quickly retreat in advance of the main German attack. It did not work. In a demonstration of pure Yankee pluck, the men of the 102nd quickly rallied and heroically fought the German soldiers back in hand-to-hand combat. Even cooks got in the fight, one running from the kitchen and killing a German soldier with a meat cleaver. The Yankee division put on a heroic defense. And after a long fight, they were able to turn the battle around, driving the Germans back across No Man’s land, through the Sybil trench and to their front line.

When the battle had ended and the air had cleared, George Preston, along with eighty other young men, was dead. “And then silence forever for the hometown kid on a shattered gray field in Lorraine, so far away from Miss Lilly’s and the quiet green fields of Dover.”

It took three years before George’s body could be returned home to Dover from his battlefield grave. Many came for his memorial service and procession to Highland Cemetery. Dover veterans, as honor Guards, accompanied the casket. Harold MacKenzie, led the caisson on horseback, with Edward Poole and Richard Breagy alongside. While passing through the center of town, they briefly paused in front of the Sanger school where George had gone as a child.

The procession slowly proceeded to the gravesite where he was interred in a place of honor. George Preston was finally home in Dover.

After the war, George’s brother Thomas Preston, who had also served in the army, returned to Dover briefly before moving to the South End, just blocks from the Home for Destitute Children. He married and worked as a cab driver until his death in the 50s. He had no children.

George’s sister Emma, who was by then known as Emily, went to Wheaton College and became a schoolteacher in Cambridge. She later married and had three daughters, Emily, Barbara and Julia - Julia named for Emily’s guardian, Julia Hunnewell. Barbara, in time, named her daughter Emily after her grandmother. This contemporary Emily was of great help in researching this article. She, too, was born with red hair like her grandmother and great-uncle George.

Lilly Mann, who had raised George from the age of four and who likely would have been the only mother he would remember, died in 1943 and is buried beside George in his grave at Highland Cemetery.

Reprinted from the Spring 2018 issue of Dover Tidings courtesy of the Dover Historical Society. Copies of the entire newsletter are available in printed form at the American Legion Post, 32 Dedham Street; the Sawin Museum, 80 Dedham Street; and the Benjamin Caryl House, 107 Dedham Street in Dover center. Digital copies are available online at www.doverhistoricalsociety.org.