[ccfic caption-text format="plaintext"]

By Shelly W. Santaniello

Hometown Weekly Correspondent

Westwood was incorporated in 1897, yet all around town, there are historic homes and evidence of historic events dating back to the colonial period. The “new” town of Westwood has an old history because it used to be West Dedham, which was settled in 1641. Some of Westwood’s historic gems are easy to spot, like the Fisher School (1845) and the Obed Baker House (1812), both located on High Street (Route 109).

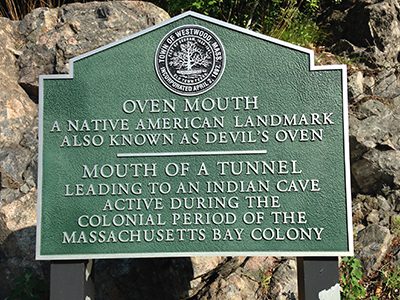

One historic marker is not as prominent, but equally as important to Westwood and New England history. It’s also on High Street, right across from Lakeshore Drive. Here sit the remnants of a Native American cave. The marker next to the cave says:

Oven Mouth

A Native American Landmark

Also known as Devil's Oven

Mouth of a Tunnel

Leading to an Indian cave

Active during the Colonial period of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

What the marker doesn’t say is that this cave was probably used during King Philip’s War, from 1675-1676. In terms of population, this short conflict between the English colonists and Native Americans was the bloodiest war in American history. Historians estimate about thirty percent of the English population in New England was killed, and about half of the Native population died due to battle, disease, and/or starvation. The loss of this war led to the eventual demise of the Native population in this area.

So, what was this war about? And who was King Philip?

The marker that stands next to Oven Mouth, a cave suspected to have been used during King Philip’s War. Photos by Shelly W. Santaniello

Soon after Wamsutta became chief in 1661, he was interrogated and imprisoned for allegedly breaking the terms of the treaty. Right after his release from Plimoth, Wamsutta fell ill and died. Metacomet believed the Plimoth officials had poisoned his older brother. With vengeance in his heart, young Metacomet became chief in 1662. He kept a tenuous peace with Plimoth for several years while secretly building up ammunition and asking other tribes to join him in a rebellion. In his words, he wanted “to push the English back into the sea.”

Metacomet’s warriors attacked first on June 20,1675, when they killed several colonists in Swansea. The colonists struck back by destroying Mount Hope, Metacomet’s royal village. (Mount Hope is in present-day Bristol, Rhode Island).

Early on, Metacomet was winning the war. He had strong alliances with the Nipmucks and Narragansetts. His men could navigate the land better than the English. They hid in swamps and caves (in addition to Westwood’s Oven Mouth, there is also a King Philip’s Cave in Norton). They relied on surprise attacks. According to the Historical Journal of Massachusetts, 52 English towns were attacked, and a dozen were destroyed. The Norfolk county towns of Medfield, Norfolk, Weymouth, and Wrentham were among those attacked. Perhaps Metacomet hid in Oven Mouth after burning one of these towns.

After a dismal start, the Plimoth colonists learned to fight in a stealthier manner. They allied with Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Massachusetts Bay colonies. They also had a few native tribes on their side. Their most powerful allies were the Mohegans and the Pequots. The tide of the war changed in the spring of 1676 when Josiah Winslow, Governor of Plimoth, enlisted an experienced ranger, Captain Benjamin Church, to hunt down the enemy.

Earlier in the war, Plimoth officials had removed all Praying Indians to Deer Island in Boston Harbor (praying Indians were peaceful natives who had been converted to Christianity by Reverend John Eliot). Captain Church assured the English allies they could win the war if they released the Praying Indians, and used them to track down the elusive Metacomet. The previously neutral Praying Indians were willing to help, probably out of desperation. They had just spent a desolate winter with inadequate food and shelter, causing over half of them to die.

It was Church’s crew of natives and colonists who found Metacomet’s hiding place in August of 1676. It was John Alderman, a Praying Indian, who shot and killed the rebellious chief. Once Metacomet was dead, the war was essentially over.

Sadly, this event also led to the downfall of Native American tribes in southeastern Massachusetts, whether they were Praying Indians or not.