[ccfic caption-text format="plaintext"]

By James Kinneen

Hometown Weekly Reporter

On Tuesday night, the Wellesley Library hosted Professor Richard D. Little, who gave a presentation titled “Dinosaurs, Dunes, and Drifting Continents: the Amazing Geologic History of Massachusetts.” He was kind enough to give more of a Wellesley-centric focus for the 135 people that showed up.

To begin, Professor Little asked how many people had been to the Connecticut Valley, before joking: “Good for you, you’re a well-travelled group.” The reason the professor asked was because he thinks the Connecticut Valley is the best place in the world to study geology and showed pictures of the things he has found there throughout his presentation.

But the presentation wasn’t about the Connecticut Valley - it was about Wellesley - so Little presented his question by giving a rundown of the questions he would be answering, including: “Where was Wellesley when the tectonic plates collided to make Pangea? What rocks are under Wellesley? And, what about the Problem Rock?”

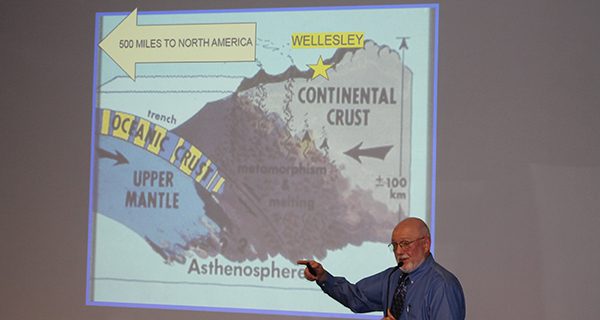

To answer the first question, Little noted that Wellesley was in Gondwana, which then rammed into North Americana. Punctuated by jokes about subduction (Little flashed a picture of a duck swimming under another duck) and orogeny versus erogenous, Little showed how various American mountains came to be and how glaciers formed the Northeast’s lakes.

As far as the second question, it is puddingstone that lies under Wellesley. Puddingstone was here before Pangea, stayed sedimentary, and was used to build various landmarks, like the Old South Church. It is also the official stone of Massachusetts.

One large puddingstone rock is the famed Problem Rock at the corner of Grove Street and Dover Road. The large rock is a “glacial erratic” adorned with a plaque that reads “Problem Rock — a Roxbury Conglomerate of the Permian Period Over 200 Million Years Old, Sometimes Referred to as Pudding Stone.” However, Little pointed out that while the plaque says it is Permian, it’s not. It is Precambrian, a fact that led a man in the audience to yell out: “I guess it’s a problem sign too!”

Little also made sure to teach everyone about armored mudballs (essentially balls of mud that gain a rock and sand shell that protects the inside), not because they were as exciting as the dinosaur footprint he had in his collection (which originated in Holyoke), but because it has been a huge part of his own research. About this, he pointed to the books he’d written and joked: “I’ve made so much money from these publications.”

After a brief question and answer period, Little let anyone that wanted to come up and touch some of his specimens, then made an even more interesting invitation to the crowd. Professor Little was looking to see if anyone wanted to join him on a tour to Iceland, which had a few open spots.

While that trip would be amazing, if you’re not that adventurous, you could always just go to the Connecticut Valley, the best place in the world to study geology.