By Audrey Anderson

Hometown Weekly Correspondent

The Davis Museum at Wellesley College is hosting two complementary photography exhibitions that focus on the beginnings of photography in the 19th century, as well as repeating subjects in snapshots of the early to mid-20th century. “Making, Not Taking: Portrait Photography in the 19th Century” and “Going Viral: Photography, Performance, and the Everyday” will run through June 7. If you are interested in the beginnings of photography and its reflections of societal trends, you will find these exhibits thought-provoking.

“Making, Not Taking: Portrait Photography in the 19th Century” focuses on the beginnings of photography, and the experience of creating portraits in the form of daguerreotypes, tintypes, and cartes de visite.

In the 19th century, photographs were created in luxurious palaces of photography, where they were exposed, developed, finished, and framed. People went to photography studios to record the important moments of their lives and photographs were treasured. The main goal of photography was to create an accurate likeness of the sitter.

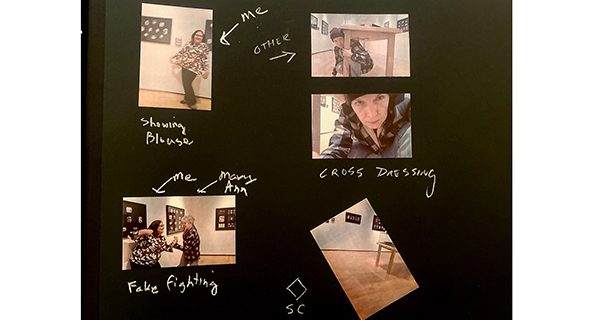

In ‘Going Viral: Photography, Performance, and the Everyday,’ an album page created by gallery visitors with the provided Kodak Printomatic cameras. Photographs by Audrey Anderson

The gallery also includes several display cases of daguerreotypes, tintypes, cartes de visite and the ornate cases that held them.

The “Going Viral: Photography, Performance, and the Everyday” exhibit continues the story of photography into the 20th century, when shorter exposure times and more accessible equipment, such as the Kodak Brownie camera, allowed people to create their own snapshots wherever they were - and to show more action, emotion, and relationship between subjects.

The Kodak Brownie camera came loaded with film; the owner would snap photos and then send the whole camera back to Kodak. The company removed the film, developed the photos, and delivered small, round prints to the customer within five days. The camera was then returned with new film loaded in it.

The snapshots in gallery are divided into several repeating types that were common in the early to mid-20th century. The prevalence of repeated types is compared to the phenomenon of photos going viral today.

Repeating types featured in the exhibit include “Viewing Vistas,” “Fake Fighting,” “Showing Skirts,” “Cross-Dressing,” “Costumes and Caricatures,” “Pyromania,” “Snapping Shadows,” “The Ends,” “Me,” and “Pictures of People Taking Pictures.” The typical explanatory signs are not included in this gallery for each of these sections. Instead, visitors are welcomed to take a card with the photo on one side and an explanation of the section on the other, bring it home with them, and continue to experience the snapshots at home.

At the end of the exhibit, Kodak Printomatic cameras are provided for visitors to use in taking a photograph for an album displayed in the gallery, and another one to take home with them. The visitors thus become part of the story.

“Making, Not Taking: Portrait Photography in the 19th Century” and “Going Viral: Photography, Performance, and the Everyday” are eye-opening, informative, and well-designed shows. In this age when we rarely even print photographs anymore, the Davis Museum allows us an opportunity to focus on the processes and the subject choices made in earlier times to create lasting records of experience.