[ccfic caption-text format="plaintext"]

A recent article in The Boston Globe told of Arlington town officials who were unhappy to discover that the state transportation department had installed two rows of metal spikes underneath a Route 2 bridge to keep homeless people from sleeping under the structure and asked they be removed. The bridge crosses the Minuteman Commuter Bikeway near the Alewife MBTA station. The spikes, which were placed in a narrow space just below the road deck where people have slept, were installed in December.

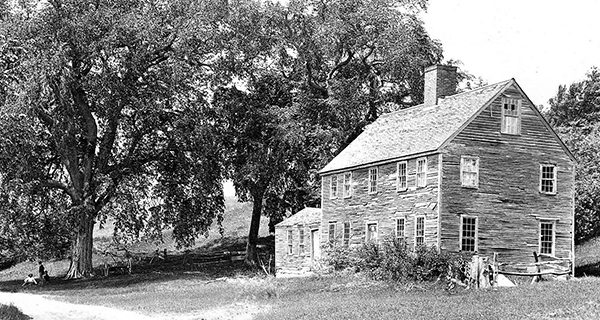

It is interesting to note in Medfield’s history a time when this town faced a serious homelessness issue. Medfield had an almshouse, or “Poor Farm,” during the late 1800s up until 1912, when it was closed. It cared for local residents, both poor and elderly. The Committee on the Care of the Town’s Poor and the Poor Farm reported that in 1892, the farm, known as the Medfield Poor Farm, was comprised of buildings, houses, and approximately 165 acres of land in the area of today’s West Street, near Bridge Street. Without any type of federal assistance or welfare programs, the care of the poor was left to the individual towns. Several elderly and very poor in Medfield stayed at the almshouse for a varying amount of time.

During this period in our nation’s history, often called the Gilded Age, there was a huge economic gap between the very rich and the poor. Because of economic downturns that began in the late 1880s, the lower end of the economic spectrum was especially hard it, causing unemployment, hunger and homelessness to increase. A major depression in the 1890s threw uncounted thousands out of work, while lesser panics and recessions in 1903 and 1907 also added to the ranks of the unemployed. High unemployment sent the jobless rate, according to some estimates, to forty percent nationwide

Medfield records show that the almshouse accommodated a surprising large, but consistent turnover of 300-400 homeless, often called “tramps,” who passed through each year, staying for something to eat or overnight and then moving on. In 1887, the local newspaper reported “the number of tramps in town were becoming more plentiful,” and in 1889 reported “the number of tramps now seen on the road had greatly increased.”

In the beginning of the crisis, Medfield tried to show them some help. In 1889, town meeting voted $124.62 to build a very basic “tramp house” attached to the almshouse, to accommodate them. Mattresses were laid on the floor for sleeping. The town library opened up the reading room and welcomed them to make use of the room, which was open every night except Mondays from 6:30-8:30 p.m. But as the numbers increased, such welcoming disappeared.

By 1890, the local newspapers had articles written about the homeless being chased out of vacant houses that they had broken into to find shelter. In 1895, five homeless men took possession of the vacant Fisher Newell house on Bridge Street and used the furniture for firewood to keep warm. Two were captured and sentenced by Judge Fairbanks to nine months at the “Bridgewater Workhouse.” So-called “tramps” in 1895 numbered more than 40,000 in the US - twice as many as soldiers in the U.S. Army.

A number of gypsies were also reported as being in Medfield on a number of occasions. They were always run out of town and were attacked in the newspapers by those of the town’s upper classes. Many gypsies often camped over the border in Millis in the Dover Road-Village Street area. Townspeople locked their children in the house out of fear of the gypsies. Parents and shopkeepers kept an eye open. Word was quickly spread throughout the town by voice and phone that gypsies were nearby.

Many a homeless man knocked at the Medfield doors looking for a handout or a job to do for some food. The Medfield Town Report notes hundreds of homeless accommodated at the almshouse. On one night, 23 homeless were “locked up,” One hundred and forty-six tramps were recorded here in 1890, 662 in 1894, another 348 in 1895, 614 in 1898, 471 in 1901, and 449 in 1903. Vagrancy laws were passed, but were generally ineffective. It also became expensive for local governments, as the jails and almshouses bulged with homeless men. In Medfield, the cost at the “tramp house” was 25 cents per individual per day.

Neighboring Sherborn’s town records describe them as “coming in upon us like an army of locusts, threatening to devour all our substances.” In 1894, Sherborn voted to build a two-celled “jail” with “no chimney to provide for the luxury of heat” for tramps to sleep.

Dedham town selectmen complained that the feeding and sheltering of the hungry homeless men drained available resources. Nearly 3,000 homeless asked for relief in Dedham in one year. According to one newspaper account, towns often decided that the best solution was to “kick the pests out of town.”

Because of a humanitarian uproar in Arlington, the Massachusetts Department of Transportation, earlier this month, removed the spike strips underneath that bridge in Arlington designed to keep homeless people from sleeping there.